By Simone McCarthy and Aishwarya S Iyer, CNN

Tue, April 16, 2024

High in the Himalayas, the people of a remote northern Indian territory fear their way of life is under threat from the changing climate, looming development – and border tensions with China.

At stake, they believe, is the future of Ladakh, one of the world’s highest elevation regions, where indigenous tribes maintain nomadic traditions on sprawling plains hemmed in by mountains punctuated by Buddhist monasteries.

For years, Lopzang Dadul herded his yaks, sheep and goats across the vast, vertiginous landscape near India’s contested border with China, following the seasons to find grazing land.

But now, Dadul says, shepherds are being barred by the Indian military from lands that for generations sustained Ladakh’s nomadic way of life – a situation he and others say has worsened following a deadly 2020 border clash between Chinese and Indian soldiers.

“In India, the army is not letting us go to places which they call no-man’s land … civilians are not allowed to go there anymore,” says Dadul, 33, a father of two from the village of Phobrang.

“If we do not get enough land we will have to sell our livestock … and look for another option.”

Ladakh’s herders inhabit what is now a highly strategically sensitive area, where India’s contested 2,100-mile (3,379-kilometer) boundary with China has for decades been a source of friction between the two nuclear-armed neighbors.

Ladakh is one of the world’s highest elevation regions, where indigenous people maintain nomadic traditions on sprawling plains hemmed in by the Himalayas. Mohd Arhaan Archer/AFP/Getty Images

“A lot of these grazing lands are in contested areas between India and China, and (after the 2020 clash) these grazing lands have now been denied to the locals, because they have been brought as part of buffer zones between India and China,” according to Sushant Singh, a senior fellow at the Indian think tank Centre for Policy Research.

Both India and China maintain a significant military presence along their de facto border, known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC), which has never been clearly defined and has remained a source of friction since a 1962 Sino-Indian border war.

Four years ago, border tensions broke out into the open when a clash in Ladakh-Aksai Chin brought the first known fatalities in conflict between the two countries in more than four decades – with at least 20 Indian and four Chinese soldiers killed.

The violence was followed by a process of disengagement, the creation of buffer zones and ongoing border talks – but the situation remains tense and neither India nor China have publicly specified where the zones are, making for a murky reality on the ground.

For that reason, the location of some of those zones may “not be clear to the local people,” said Manoj Joshi, a distinguished fellow at the New Delhi think tank Observer Research Foundation.

The movement of herders is seen as sensitive because both countries have in the past used their presence in an area to assert military control over it, said Singh.

“First graziers go, then you pitch up tents, and then your soldiers reach and then you say ‘this is our area,’” he said, noting why India is blocking them from entering these zones.

Konchok Stanzin, a local councilor, has been trying to raise awareness about the impact of land restrictions on nomadic herders for years. Courtesy Konchok Stanzin

Konchok Stanzin, 37, a councilor in Ladakh’s Chushul constituency, which encompasses four border villages, says such restrictions have impacted herders’ access to land.

“Rezeng La, Mukhpari, Black Top, Helmet Top and Gurung Hill. All these areas are winter grazing areas of Chushul village. Now people find it very difficult to go there. These areas are now no-man’s land,” said Stanzin, who has been raising awareness about these issues since 2020.

But those interviewed by CNN also point to what they say is the impact of Chinese encroachment and changes to the control of contested lands over time, including from the 2020 clash.

“We know the reality, we know the ground situation. If the (Indian) government says we have not lost an inch of land, then whatever we have lost is already lost,” said Stanzin.

Dadul in Phobrang said the “Chinese are coming toward us constantly. They have been crossing the line and coming in,” he said. “China is capturing the land, the Indian government is saying nothing is lost, the (Indian) Army is not letting us go there.”

CNN was unable to independently confirm the status of the restricted land described in this report, nor claims of Chinese encroachment or loss of Indian territorial control after the 2020 clash.

In a statement, India’s Ministry of Defense told CNN: “No Indian territory has been lost during the standoff. Negotiations are currently underway for disengagement at the remaining friction points.”

On the buffer zones, the ministry said: “all disengagements achieved till date have been based on the principle of Mutual and Equal Security. Currently, a mutually agreed moratorium exists on military activities from both sides in areas where disengagement has been affected, to maintain peace and tranquility.”

The “number of Indian graziers and livestock in traditional grazing areas has seen a sharp rise” after the events of 2020, the ministry’s statement added. “There has thus been no adverse impact on the livelihood of locals in the area.”

China’s Defense Ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

Video Ad Feedback

Explained: Why do India and China spar at the border? (2022)

02:40 – Source: CNN

Protest and hunger strikes

Mounting concern over threats to the way of life in Ladakh – from lost grazing lands to climate change and industrialization – have driven thousands from across the region to its joint capital city of Leh in recent weeks to demand greater rights ahead of India’s general election, which begins Friday.

There, some 3,500 meters (11,550 feet) above sea level, residents are calling for Indian statehood for Ladakh to ensure political representation, as well as inclusion in the national constitution’s Sixth Schedule, which grants special rights to tribal areas. Organizers say at least 10,000 people turned out during a single day in Leh last month to support the start of an ongoing, weekslong hunger strike.

Ladakh lost special controls over its land in 2019, following a controversial move by the Indian central government that stripped the former state of Jammu and Kashmir of its statehood and broke off Ladakh, which had been a part of it, into a separate territory.

The change placed the region under the direct control of India’s central government, which critics say has pared back national environmental protections and backed ecologically harmful infrastructure development pushes in other sensitive parts of the country in recent years.

Protesters gather in Leh to join and support a hunger strike calling for attention to environmental threats and more rights and protections for the territory. Courtesy Sonam Dorje

China doesn’t recognize what its Foreign Ministry has called the “so-called union territory of Ladakh,” saying the “western section of the China-India border has always belonged to China.” In addition to China, the territory of Ladakh also shares a disputed border with Pakistan, another neighbor with which New Delhi has fraught relations.

Now many in Ladakh are concerned about the potential damage of future New Delhi-backed industrial projects, or that an influx of people moving in could shift the largely tribal demography.

“Only local people will think about the next few generations, (others will) … make mistakes at best and sell off the place at worst,” said Sonam Wangchuk, an activist and educator widely known across India, who is leading the hunger strike to draw attention to environmental threats facing Ladakh.

Speaking to CNN during the 19th day of a 21-day fast last month, Wangchuk said in a steady but weakened voice that without protections and representation, “we will have no control on how to secure these mountains.”

He pointed to plans for a solar plant and the potential for more environmentally damaging industry to follow.

Environmental activist Sonam Wangchuk kicked off the ongoing climate fast in March. Courtesy Sonam Dorje

The activism has faced pressure from local authorities.

Earlier this month, Wangchuk and other civil society leaders called off a planned peaceful march toward the border they said was meant to reveal grazing lands lost to Chinese encroachment, after local authorities banned unauthorized gatherings and temporarily slowed internet speeds, citing an “apprehension of breach of peace.”

CNN has reached out to Leh’s district magistrate and local police for comment.

Some, like the Ladakh president of India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), say protections on land, jobs and culture in Ladakh could be granted through other means, which local leaders have rejected. He also suggested the border dispute is a factor in why other demands won’t be met.

“We are with the border with China and Pakistan. How can a sensitive (place) like Ladakh just be turned into a state immediately?” the local party leader, Phunchok Stanzin, told CNN.

‘Way of life is going away’

The nomadic traditions of shepherd communities living off the land and selling goats’ wool to be spun into luxurious Pashmina had already been diminishing in Ladakh in recent decades.

A tourism boom and the impacts of climate change – as receding glaciers and other impacts drive flash floods, drought and reduced snowfall – are among factors shifting how some families make their livings.

Namgail Phonchok, 51, whose village lies south of the piercing blue waters of Pangong Lake that stretches from India into China, fears his children won’t be able to continue their way of life – including due to access restrictions on grazing lands.

“When they won’t let us graze, then we will sell our animals. We do not know what other job to get, and our own work will also go, then what will we do?” he said, adding that “if big industries come here then the environment will get ruined completely.”

Between longer-term changes and new restrictions on grazing lands, “our nomadic way of life is going away,” Phonchok said.

Lopzang Dadul, 33, says if herders don’t get enough land they will have to sell their livestock and abandon their way of life. Courtesy Lopzang Dadul

Dadul, in Phobrang, has seen those changes too.

He says 60 of the 113 households in his village used to be nomadic; now only 10 are maintaining the tradition due to those factors and lost grazing lands.

“Nomadic way of life is a very rare thing in India. In one home you have yaks, sheep, goats, horses and other livestock … yaks are meant for transportation and milk, cheese and butter, and the goats give Pashmina. This is the actual eco-friendly and sustainable way of life,” he said.

“When the army steps back from the real border, this effect spills over to the village … and the movement of the nomadic tribes is restricted,” he added.

New Delhi has denied that its border tensions with China are impacting the lives of the shepherds there.

Supporters and participants of the ongoing climate fast gather in a memorial park in Leh, Ladakh. Friends of Ladakh

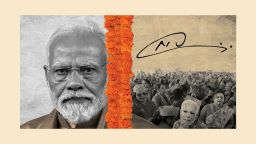

And Prime Minister Narendra Modi – India’s Hindu nationalist leader, who is widely expected to win a rare third term in the upcoming election – has tread cautiously around the border issue, claiming in the wake of the June 2020 border clash that “no one has intruded” into Indian territory.

Modi’s comments appeared to contradict his own foreign minister, who said the violence began after “the Chinese side sought to erect a structure in Galwan valley on our side of the LAC.” Beijing at the time said, “none of the responsibility lies with China,” blaming Indian troops for “starting provocations” and crossing the de facto border.

New Delhi says two sites remain contested along the Ladakh border after disengagement at other contested zones following the 2020 clash. Observers believe Chinese forces are blocking Indian patrols in those contested areas where they previously had access.

At the points where there has been disengagement, the establishment of buffer zones means “both sides have pulled back by mutual agreement and neither side patrols there,” as opposed to earlier, when troops could patrol up to their claim, according to Joshi in New Delhi.

‘Real protectors’

New Delhi’s official response – and the lack of transparency over buffer zones – has fueled domestic debate about India’s position on the border.

A report from a Ladakh police superintendent released in 2023 further stoked concerns – detailing how Indian forces lost their presence in 26 of 65 patrol points over an unspecified period. Reduced patrolling led to an ultimate loss of control over such areas, where China grabs land “inch-by-inch,” the report said.

The report also accused China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of having “taken advantage” of the buffer areas established in the de-escalation talks by objecting to Indian forces’ movement in the buffer zone and asking for further pushback.

It noted: “Much restrictions on the movement of civilians and grazers near the forward areas on the Indian side, indicating their ‘play safe’ strategy that they do not want to annoy the PLA by giving them the chance to raise objections on the areas being claimed as disputed.”

An Indian Army vehicle passes through the Zoji La mountain pass along a highway connecting Jammu and Kashmir to Ladakh. Waseem Andrabi/Hindustan Times/Getty Images

A copy was posted online by Indian magazine The Caravan alongside a report from Singh, from the Centre for Policy Research.

Singh, who is also a lecturer at Yale University, suggested the lack of clarity on the border situation may stem from Modi’s concerns over Chinese military superiority – and tarnishing his government’s image.

If Modi’s strongly nationalist government were to acknowledge loss of territorial control, “it would be very difficult for him to then not take some aggressive action to regain that lost territory,” he said.

“Then the risk of escalation would be very high and, in that escalation, I think Mr. Modi’s government fears that they could be humiliated – that they could lose to China.”

But some from Ladakh argue that the sensitivity of the region, both environmentally and strategically, is the very reason to allow the local people more control over the land – including access around the border.

“The shepherd is going to the mountain and protecting it every day,” said Dadul, the shepherd from Phobrang.

“If the real protectors are brought to the borders and allowed to stay there, then what is left will be protected.”